Michael Hecker and Bärbel Friedrich: “It’s a German-German success story”

“It’s a German-German success story”

It was 35 years ago, but many people still remember 9 November 1989. How did you, Professor Friedrich and Professor Hecker, experience the event?

Friedrich: I was in Berlin and watched the news on television. The next day, I took part in a rally with my working group in front of Schöneberg Town Hall. It was said that what belongs together is now growing together – the atmosphere was moving. We had the feeling that we were right at the centre of history.

Hecker: I came from Bayreuth, sat on the train to Greifswald and knew nothing about it. It wasn’t until I got home that my wife told me what had happened in Berlin.

You were in West Germany on the day the Wall came down. How did that happen?

Hecker: It really was a strange coincidence. In almost twenty years as a researcher in the GDR, I was only allowed to travel to the West twice to give lectures and meet colleagues. I wasn’t in the party and I wasn’t a travelling cadre. The first time was in Hamburg in the summer of 1989. The second time, colleagues invited me to the University of Bayreuth at the beginning of November. I would never have expected that the Wall would fall just then.

How do you remember the days after 9 November?

Hecker: There was a great deal of excitement and a spirit of optimism in my institute, the situation was heated. Nobody knew what was coming.

Friedrich: I’ll never forget the Trabi parade on the Kudamm and a cycle tour across the Glienicke Bridge to Potsdam. We thought the Cold War was over and the mood was euphoric.

@ Peter Binder

Visiting Greifswald: In the early 1990s, Bärbel Friedrich and her husband Cornelius Friedrich visited the laboratory of Michael Hecker (right). In conversation, the Greifswald microbiologist explained, among other things, an early method for separating proteins.

What happened in science?

Friedrich: We immediately invited our East German colleagues to visit institutes and to the annual conference of the Association for General and Applied Microbiology, VAAM. It happened to take place in Berlin in March 1990.

Hecker: As the last president of the GDR Society for Microbiology, I was allowed to give a welcoming address at the VAAM conference in question, during which – I was extremely emotionally tense – I lost my voice several times. Just one year later, the two societies merged at the follow-up conference in Freiburg.

Much has already been said and written about the turnaround in science. What is special about your new book?

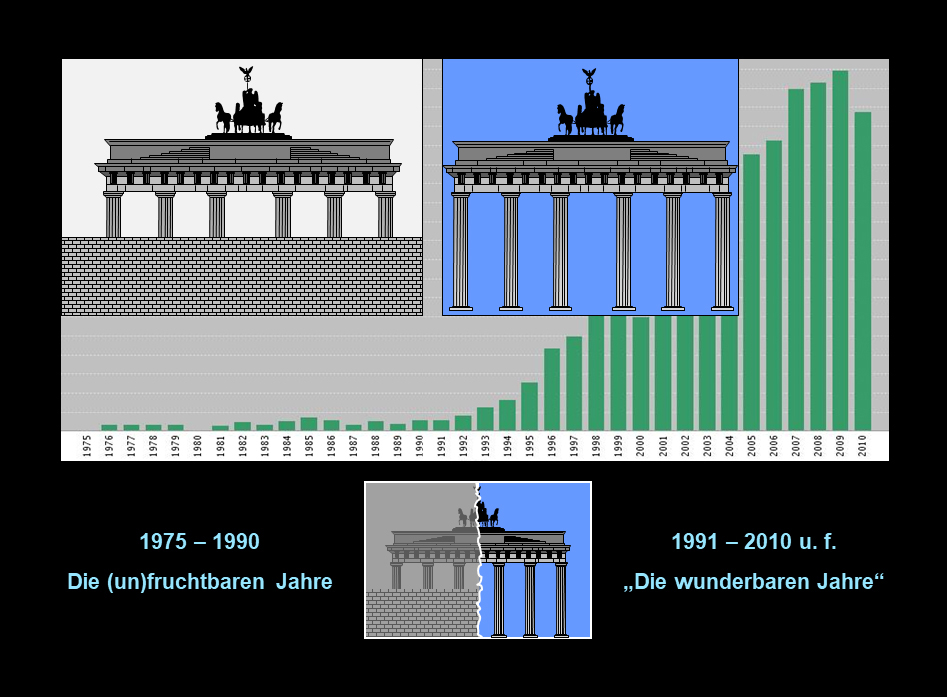

Hecker: We are focussing on research at universities, especially developments in the life sciences. Our book describes how the life sciences in East Germany, which had been completely left behind, were brought up to international standards surprisingly quickly. A lot of negative things have been written about the general development since reunification. We present a positive example, a German-German success story. This also deserves to be heard.

Friedrich: For us, science is a prime example of successful integration between East and West. That is one of the most important statements in our book. The discussion about science at East German universities is currently out of kilter. Our aim is to bring it into balance.

Before we come back to this topic, let’s outline the three phases that you describe in detail in your book: the years from 1965 to reunification, the 1990s as a transformation phase and the period of consolidation from 2000 to the present. What was the state of microbiology in the GDR before 1989, Mr Hecker?

Hecker: We sat behind the Wall and looked enviously to the West, where the great discoveries in biology were being made. We lacked the equipment, the expertise, the whole environment. But we had excellent young people with whom we conducted passionate research despite the poor conditions. There were many interesting, atmospheric conferences that I remember fondly. For example, on the island of Hiddensee. There, in the summer of 1985, we buried the genetic engineering of the GDR in an urn on the beach in the name of the father, the clone and the holy splicer because of the lack of chemicals.

Friedrich: I am a child of the sixties and lived through the student riots. Back then, Göttingen was the Mecca of German microbiology and a springboard to America. At MIT I learnt the latest methods in molecular biology and experienced an open, yet competitive environment. When I returned to Germany at the end of 1976, I had to fight: there were hardly any positions for young scientists and only limited research funding. The competition was tough.

Hecker: We didn’t realise that at the time. They were sitting in paradise and we were on the outside – that’s what we thought.

Friedrich: In the end, I was lucky and decided to take up a professorship at the Free University of Berlin. I started there in 1985 with the establishment of a new science-orientated microbiology department. The students were very motivated, it was a good, exciting time.

The transformation phase began with the fall of the Berlin Wall. How did it come about, Mr Hecker, that you became Dean of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences in Greifswald?

Hecker: I was more or less forced into it. I actually wanted to go out into the world to catch up with modern research. Instead, I had to help reorganise our university according to the FRG model. It was an exhausting four years. The majority of professors were not taken on, some for reasons of age, others because of professional deficits or because the findings of the Honours Commission spoke against it. There were many layoffs, particularly in the humanities and social sciences. When it came to subsequent new appointments, the picture in Greifswald was similar to that at most East German universities: around two thirds of the new appointees were East Germans, including habilitated junior academics. There were significantly fewer in the humanities. If we had had more qualified applicants from East Germany, the proportion would probably have been even higher. Nevertheless, it was urgently necessary for colleagues from the West to come to us with their international experience. On balance, there can be no question of the West colonising the East.

@ Design: Sabine Schade

In the bestseller by Leipzig literature professor Dirk Oschmann, “The East: a West German invention”, it sounds quite different.

Hecker: Mr Oschmann addresses disappointed East Germans with his book, he wants to provoke. But when it comes to the sciences, he doesn’t have an overview. He writes from the perspective of a humanities scholar. The generalised statements do not apply to the life sciences and medicine. He writes, for example, that East Germans can be found among secretaries or technicians, but hardly among professors. According to the book, he had to deny his East German identity in order to be accepted as a scientist in the West – something like that never happened to me. The claim that the East has been overrun by the West in the field of science is nonsense. On the contrary, the figures from the DFG Funding Atlas show that the amount of funding provided in East Germany is completely in line with the amount spent at West German universities.

Mrs Friedrich, you experienced the period of reunification in Berlin, first in the western part of the city, then in the east. How do you remember those years?

Friedrich: In view of the challenges posed by the unification of the two parts of the city, money was tight and the time pressure was great. There were dramatic cutbacks, and the West Berlin universities also had to cut back. By 2010, around 350 of the 500 professorships at Humboldt University had been filled after being advertised – as many as 220 of the new professors came from the East.

It is often said that the academic system in the Federal Republic was transferred one-to-one to the East. Is that true?

Friedrich: In the beginning it was like that, everything had to happen very quickly. But there was a huge backlog of reforms in the West even before reunification. Reforms finally came in the 1990s, partly as a result of the Bologna Process. Towards the end of the decade, more money flowed into the science system and the DFG was able to develop the forerunners of the Excellence Initiative, the DFG Research Centres, and later the Clusters of Excellence. I was Vice President of the DFG at the time and experienced a great deal of openness towards the universities in Eastern Germany. There was also a great willingness to help East Germany in the Wissenschaftsrat and in federal research committees. Looking back, there were major changes in the German science system as a whole during this phase.

Please briefly outline the developments in your fields since 2000, during the consolidation phase.

Hecker: The young scientists at my institute, who swarmed out into the world immediately after 1990 with funding from the DFG, finally brought the expertise we lacked to Greifswald. With the new knowledge and in good co-operation with microbiologists from all over Europe – including Bärbel Friedrich, Jörg Hacker and many others – we were able to establish a reference laboratory for microbial proteomics. This enabled the universities in the East, which had been left behind for many years, to work very quickly according to international standards.

Friedrich: This collaboration was also extremely fruitful for my research group. We were integrated into large networks for genome research on microorganisms. There were many joint publications. In Greifswald, the Krupp Wissenschaftskolleg actively supported the East-West collaboration. The establishment of the college was initiated by the Essen-based Krupp Foundation in 2000. A special event was the establishment of a doctoral programme together with Israel.

The East German universities have caught up considerably in the current competition for excellence. Ten initial applications for clusters of excellence were assessed favourably –- more than ever before. Does it take a generation to keep up in the top league?

Hecker: That may be the case across the board. But in some places it happened much faster. Dresden has been a scientific beacon since reunification. Jena, with its outstanding non-university institutes, also caught up quickly. Both locations have been doing very well in the competition for excellence for some time now. It should be emphasised that the research projects were initially mostly shaped by newly appointed researchers from the old federal states. In the meantime, however, a new generation has grown up that is unfamiliar with the often overused East-West debate. Many of them have been able to make a name for themselves professionally in renowned laboratories around the world after completing their doctorates. They receive highly attractive job offers and their CVs are similar to those in the West. As a result, the issue of East-West is becoming increasingly blurred with the younger generation.

This year sees state elections in Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg. The AfD is likely to do well in all three states. What consequences would that have for science?

Friedrich: It could be catastrophic. A strong influence of the AfD would severely restrict the freedom and internationality of science – and these are the very foundations of successful research. The AfD denies climate change and the coronavirus facts. This is not compatible with a modern, evidence-based scientific world view.

Hecker: I take a similar view. Banning the party would not achieve much. We have to counter the AfD with arguments and convince people of the necessity and benefits of free science.

@ Peter Binder

@ Vincent Leifer

ABOUT THE PERSONS

Bärbel Friedrich was born in Göttingen in 1945. After completing her doctorate in microbiology at the university there, she went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for two years as a postdoctoral researcher and then habilitated in Göttingen. In 1985, she became Professor of Microbiology at the Free University of Berlin; in 1994, she moved to the Humboldt University, where she became Professor Emeritus in 2013. Her research focused on physiological and molecular biological studies of bacteria that grow with hydrogen as an energy source and use carbon dioxide to synthesise cell substance, which is documented in more than 200 original papers. From 2008 to 2018, Bärbel Friedrich was Director of the Alfried Krupp Wissenschaftskolleg, which supports the University of Greifwald and the science region as a whole. She was also Vice President of the Leopoldina (2005 to 2015), Vice President of the German Research Foundation (1997 to 2003) and a member of the Wissenschaftsrat (German Science Council, 1997 to 2003). She has received numerous honours, including the Arthur Burkhardt Prize (2013), the Federal Cross of Merit (2013), the Leopoldina Medal of Merit (2016), membership of the Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art (2021) and an honorary doctorate from the University of Greifswald (2022). Bärbel Friedrich was a member of the GDNÄ board from 2001 to 2004.

Michael Hecker was born in Annaberg in the Ore Mountains in 1946. He studied biology at the University of Greifswald, where he gained his doctorate in 1973 with a thesis on the biochemistry of plants. In the years that followed, he devoted himself primarily to researching the proteome, the totality of all proteins in a living organism, tissue or cell. Michael Hecker was Professor of Microbiology from 1986 to 2014 and Director of the Institute of Microbiology there from 1990 to 2013. As Dean, he made a significant contribution to the reorganisation of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences from 1990 to 1994. From 1997 to 2001, he was President and Past President of the Association for General and Applied Microbiology, the largest association of microbiologically orientated scientists in the German-speaking world. Michael Hecker has received several science awards and an honorary doctorate from the University of Göttingen in 2023. He is an elected member of several national and international academies, including the American Academy of Microbiology, the European Academy of Microbiology, the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina and the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

@ mdv

Title page of the new book “Die ostdeutschen Universitäten im vereinten Deutschland”. Ernst-Ludwig Winnacker, President of the DFG from 1998 to 2006, wrote the foreword and afterword.

Book

Michael Hecker, Bärbel Friedrich: The East German universities in a united Germany. A success story from an East-West perspective (with foreword and epilogue by Ernst-Ludwig Winnacker), 345 pages, Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Halle (Saale) 2023