Paul Mühlenhoff: If you don’t think for yourself, you don’t learn properly

“If you don’t think for yourself, you don’t learn properly”

Paul Mühlenhoff, head of the GDNÄ student program, on amazing experiences with ChatGPT, attempts at cheating at school and discussions in the staff room.

Mr Mühlenhoff, there has been lively discussion about ChatGPT for months. Do you have your own experience with the text generator?

I tried ChatGPT for the first time in late autumn 2022 and found the program surprisingly good, even in the then still early version. I asked practice questions for an upper school lesson on the novel “Der Trafikant” – just for testing purposes, not for a concrete application. The results came very quickly, were quite challenging and seemed to be suitable for the target group. I found it impressive that the program told me what it didn’t know yet. Despite some shortcomings, it was already clear then where the journey was going: these systems will get better and better.

In the debate about ChatGPT in schools, some call for a ban, others emphasise the new opportunities. What is your position?

In my opinion, a ban would be pointless. ChatGPT and other generative language models are coming and we have to deal with them. Our job as teachers is to explain how it works and to prevent abuse.

According to a survey by the digital association Bitkom, half of the students in Germany have already used ChatGPT when doing homework, writing texts or preparing for exams. What is it like at your school?

At my school, the Helmholtz-Gymnasium in Bielefeld, ChatGPT is mainly used in the upper school. I don’t know exactly what the situation is like in the middle school. I suspect that it doesn’t play a big role there yet.

© Timo Voss, Studio of Thoughts | Helmholtz-Gymnasium Bielefeld

Bielefeld’s Helmholtz High School, shown here in an aerial photo, was founded in 1896. Under the motto “A modern high school with tradition”, around 100 teachers now teach around 1000 students.

For what purposes do the young people at your school use the chatbot?

As far as I can observe, mainly to try it out and play. However, there have already been individual cases of suspected misuse this year. For example, it was a question of subject papers, i.e. papers that are written at home without school supervision and whose grade is weighted the same as an exam grade. If there are clear discrepancies between the work and the previous performance, we naturally become suspicious.

How did your school react in this situation?

Since we have the burden of proof, colleagues scrutinised the work very closely. Knowing that ChatGPT can also generate source references, they checked, for example, whether Bielefeld libraries had the books mentioned in the paper. The suspicion that papers were written with the help of other people, such as parents, also existed in the past. But ChatGPT opens up completely new dimensions. For this reason, there is already a discussion in our staff about whether papers of the previous type will be acceptable at all in the future. Will they have to be supplemented by oral examinations or will we have to find completely new ways?

It will probably be the same in other schools. How are the school authorities reacting to the challenge?

The Ministry for Schools and Education in North Rhine-Westphalia reacted quickly and published a well-done guide for dealing with text-generating AI systems. Other federal states have also published corresponding recommendations.

What about teacher training on AI in general and chatbots in particular?

There are such offers. But they would only be interesting for me if they were specifically tailored to my subjects of German and biology. That is not yet the case.

You tested ChatGPT early on. Did that have consequences for your teaching?

Yes, I promptly made the new technology a topic in my upper school lessons. We talked about how chatbots work, what they can and cannot do. We also talked about the uncertain source situation and data protection concerns: After all, you have to give out your mobile number to use ChatGPT extensively. However, my main concern in the conversation with the students was to warn them early on about the temptation to use the AI model as a “homework helper”. Using it would be beneficial in the short term, but if you don’t think for yourself, you won’t learn properly. And that is the danger behind it. But then we didn’t continue to use ChatGPT in class.

Can you and your colleagues tell whether a homework assignment was done by students or by a chatbot?

So far I haven’t had any suspicious cases. I would argue that we teachers can tell pretty quickly whether it is our own performance or not. We can assess the performance of our students very well through their participation in class and the exams – discrepancies are quickly noticed. In my subjects, I hardly see any scope for using ChatGPT for homework anyway. They usually involve material with texts and graphics, and you can’t easily feed the AI with that yet. With simple definition tasks, it is perhaps something else. But these are not of great importance for us.

In what way could ChatGPT be useful in your subjects?

That’s a difficult question, because the areas of application are incredibly extensive and many questions are still unanswered for us teachers. I see a possible use especially where the students are in dialogue with the AI and have to formulate their prompts, i.e. their requests, more and more precisely in order to reach the goal. Learning then takes place in this process. In biology, for example, it would be conceivable to first develop experiments hypothetically or even to model an experimental procedure. In German, for example, I would find it exciting to have the AI interpret specific dialogues from a novel or drama excerpt and to discuss the plausibility of the reasons with the students. Can an AI grasp irony? How much context does it need for that? Answering these questions would also be useful for our own understanding of literary texts.

Will ChatGPT fundamentally change schools, as some predict?

No, I don’t think so, at least not in the classical school subjects. It might be different in computer science classes. What certainly remains unaffected by the new technology is our mission as teachers: we are supposed to educate young people to learn independently and impart knowledge. ChatGPT can possibly help with this and enrich the lessons, especially in the upper school.

© MIKA-fotografie | Berlin

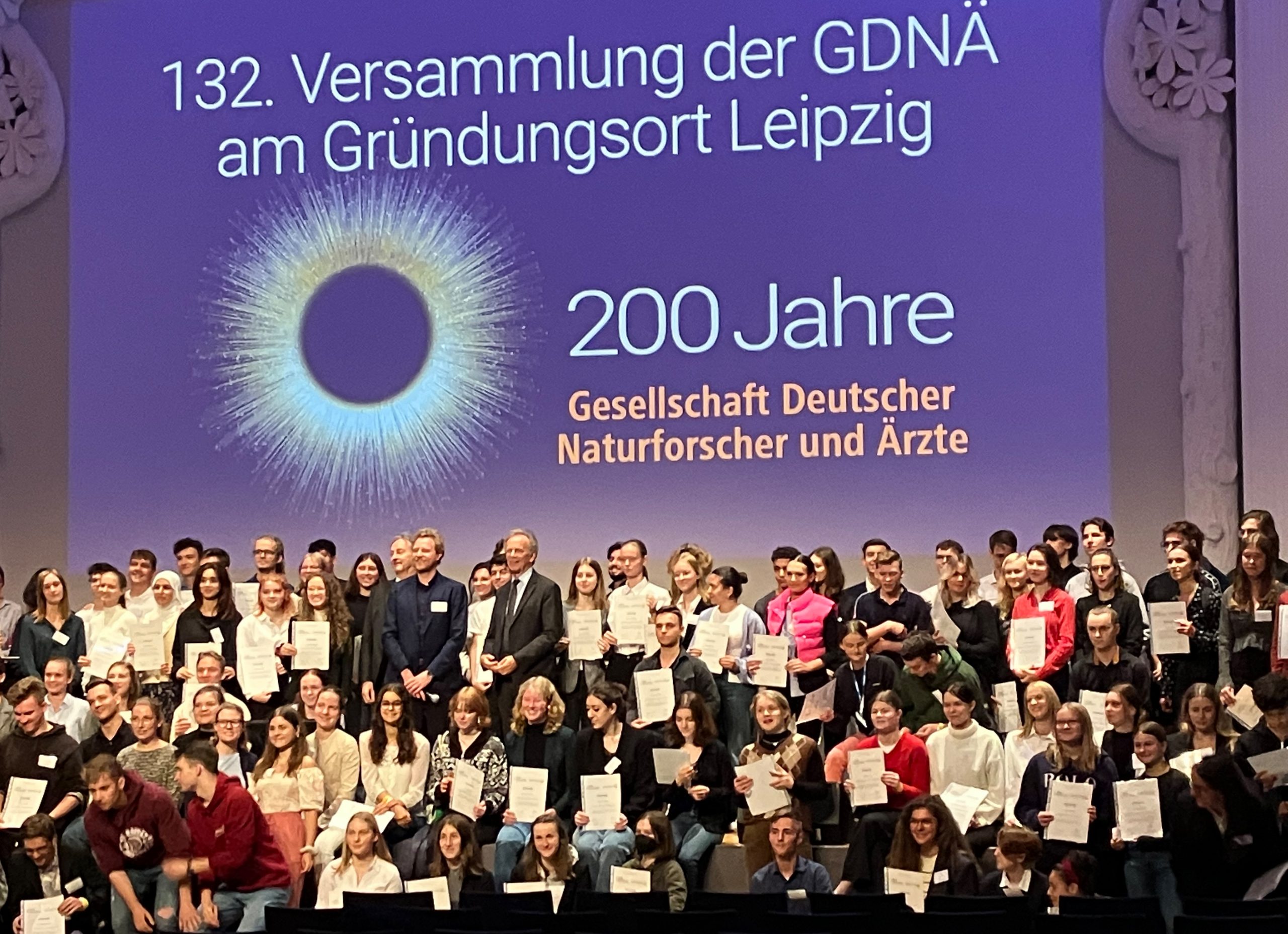

Grand finale of the 2022 Student Program on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the GDNÄ in Leipzig. Paul Mühlenhoff is is in the middle of the second row from the top.

The students always deal with questions that they have formulated themselves – this will also be the case in Potsdam in 2024. There are no guidelines from the student program, neither in terms of content nor methodology. I can well imagine that ChatGPT will be used for research in the future. And I am convinced that the students will disclose their approach transparently.

© Stefan Diesel

Paul Mühlenhoff is a high school teacher of German and biology.

About the person

Paul Mühlenhoff is in charge of the large-scale students` program of the German Society of Natural Scientists and Doctors. The teacher of German and biology worked for many years at the XLAB – Göttingen Experimental Laboratory for Young People. Since 2019, he has been teaching grades 5 to 12 at Helmholtz Gymnasium in Bielefeld. The school was founded in 1896 and describes itself as a “modern school with tradition”. Around a thousand students and a hundred teachers come and go there every day.

Further information:

What is ChatGPT? – Answer from the editors

ChatGPT is a chatbot that has an answer to every question and seems to know everything. A chatbot is a language model that can “talk” to humans in natural language, provide information and write and rephrase texts. The language model is based on artificial intelligence (AI). It calculates the probability with which words follow each other and forms sentences from this. In order to be able to imitate human language, the software was trained with a large amount of texts. ChatGPT can deliver excellent results if you ask good questions. But it can also spout nonsense with the greatest of ease. It is therefore important to fact-check the answers. The “chat” in the name refers to the program’s ability to converse with users in natural language, the abbreviation GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer. The chatbot was developed by the Californian company Open AI.

What is ChatGPT? – Answer from ChatGPT

ChatGPT is an advanced AI model based on the GPT 3.5 architecture developed by OpenAI. It specialises in interacting with users in natural language and helping them answer questions or solve problems. ChatGPT can understand text input, understand and generate context, and generate human-like responses. It has been trained through machine learning on large amounts of text data to gain broad knowledge in different topics. It is able to carry on conversations, give instructions, provide information and much more.

(Result of a query on 4 July 2023)