“In free speech and friendly solidarity”

Born in the spirit of awakening, the GDNÄ has always been a forum for great debate and thoughtful analysis. How it has managed this over almost two centuries is described here by the historian of science Dietrich von Engelhardt.

Professor von Engelhardt, next year the GDNÄ will be 200 years old. Not all science organisations last that long. How do you explain the robustness of the GDNÄ?

First and foremost with its uniqueness – also in comparison to other scientific societies. Since its foundation in 1822, its core concern has been the interdisciplinary exchange between natural scientists and medical doctors as well as the connection to philosophy and society. In the humanities, this interest in other disciplines is not as pronounced; there is no comparable overarching humanities society. What also stabilised the GDNÄ were the great scientific debates that took place at its meetings and that radiated far into society and culture.

Which debates are you thinking of?

For example, the debates on natural science and natural philosophy, on the freedom of research, Darwin’s theory of evolution, mechanism and vitalism, and on popularisation and school education. I am thinking, for example, of Emil du Bois-Reymond’s speech at the 45th Assembly in Leipzig in 1872 on “The Limits of Natural Knowledge”, which dealt with the relationships between force and substance, body and soul, which, in his view, were fundamentally not discernible by natural science. The speech provoked both agreement and opposition – just like Ernst Haeckel’s advocacy of Darwin and Darwinism. Rudolf Virchow’s plea for the freedom of science and for the renunciation of the dissemination of the unproven in school lessons and in public also triggered a variety of reactions.

The GDNÄ as a forum for great debates: can it still do that today?

Today there are many other platforms for the competition of ideas, the GDNÄ has got strong competition. Its heyday was certainly in the 19th and early 20th centuries. But I also see great opportunities for the GDNÄ in our time, be it in the field of education or in the dialogue between disciplines and in its relationship to society and culture. The response of many meetings has shown this impressively and repeatedly. In this perspective, an important and high-profile topic is also “Image in science”, which will be the focus of the 2022 Assembly in Leipzig.

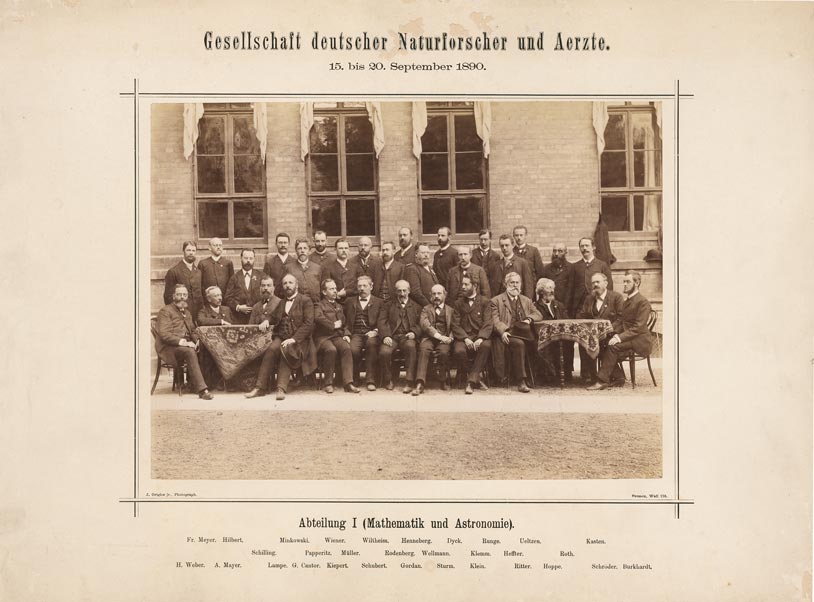

© Deutsches Museum, München, Archiv, CD79207

The Mathematics and Astronomy Section at the 1890 GDNÄ meeting.

Let us go back to the beginnings. The first meeting of the GDNÄ took place in Leipzig, in the autumn of 1822. What were the founders concerned with?

The driving force was the natural scientist and natural philosopher Lorenz Oken. He had gathered a group of like-minded people around him, including the romantic natural philosopher, painter and physician Carl Gustav Carus and the chemist and mythologist Johann Salomo Christoph Schweigger. Once a year and always in a different city, hence the epithet Wandergesellschaft, they wanted to inform each other about the state of their own research – in free lecture and friendly solidarity, but also in open discussion. The founders were concerned with lively exchange, also as a counter-design to the rituals of the universities and academies of science that had existed for a long time at that time.

Did they succeed in this from the beginning?

As far as can be deduced from the sources, yes. Oken’s call for the Assembly of German Natural Scientists was answered by 13 natural scientists and physicians as members at the first meeting in 1822; a total of 60 people took part in the lectures and discussions. Later it became much more, occasionally 5000 to 7000 visitors came. In the present, the numbers of members and visitors have declined again – younger scientists are setting other priorities for their careers and research. In the early years, the lectures, entirely in the spirit of the romantic philosophy of nature, were about the unity of nature, the connection between nature and spirit, man’s responsibility for nature and also about social commitment. After lively and sometimes controversial discussions, the days came to an end in convivial company with witty table speeches and joint singing.

Could it be sustained like that?

Not quite. In 1828, there was a profound structural change and indeed the first crisis. In his speech at the Berlin Assembly, Alexander von Humboldt had strongly advocated the formation of sections in addition to the general sessions, in order to be able to respond appropriately to scientific progress in the individual disciplines and in divergent debate. This initiative was to prove immensely important for the continued existence of the Society, but was initially met with resistance. Some feared a drifting apart of the disciplines, a development that the founding of the GDNÄ had been intended to counteract. Lorenz Oken was also not at all enthusiastic about the division into sections, but it was finally accepted. However, the commonality was by no means completely abolished: the local newspaper wrote about the evening get-together at the 67th meeting in Lübeck in 1895: “One dined I sections and sang together.

How did Oken react?

He withdrew somewhat and no longer attended all the meetings. His own activities and commitments took a toll on him in those years. Oken was a committed, pugnacious man who strove for a united Germany, fought for freedom of the press and courageously stood up to his opponents – even if they were sovereigns or named Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. He wrote and published a great deal, campaigned for science education in schools, edited the first interdisciplinary scientific publication “Isis oder Encyclopädische Zeitung” – it appeared from 1819 to 1848 – and finally went to Zurich. There he was appointed the first rector of the university and died in 1851.

© Deutsches Museum, München, Archiv, CD85577

View of the auditorium at the celebration of the 150th anniversary of the GDNÄ in Munich in October 1972.

At that time, the GDNÄ was thirty years old. How was it doing?

The GDNÄ was doing very well. Its meetings were highlights of scientific and it united the scientific and medical elite of Europe. The lectures, which were printed in proceedings, reflected the development of natural sciences and medicine in the 19th century. Researchers from Italy, England, France, Russia and other countries came to the meetings, even if this was not politically safe for some. Inspired by the GDNÄ’s example, similar societies were founded abroad: in 1831 the British Association for the Advancement of Science, two years later the Congrès Scientifiques de France and in 1839 the Italian Riunioni degli Scienziati Italiani. In Germany, numerous scientific and medical societies emerged from the GDNÄ – in physics as well as in chemistry, pharmacy, pathology, gynaecology, surgery and psychiatry.

The 20th century was marked by war and reconstruction. How did this affect the GDNÄ?

During both world wars, meetings were suspended. During the Third Reich, the situation was extremely complex in the three assemblies in 1934 in Hanover, 1936 in Dresden and 1938 in Berlin. In their welcoming speeches, the First Chairmen affirmed the new Nazi era, sometimes with opportunistic rhetoric, sometimes with inner conviction. They dealt with the relationship between German and international research in different emphases, spoke of an orientation towards the national welfare and the benefit for mankind, and at the same time gratefully emphasised the participation of foreign scientists. The scientific and medical lectures were predominantly free of Nazi ideology, although the lectures on hereditary biology certainly corresponded to the racial ideological discussions of the time. Overarching lectures, such as those by Werner Heisenberg on “Changes in the Foundations of the Exact Sciences in Recent Times” in 1934, by Walter Gerlach on “Theory and Experiment in Exact Science” in 1936 or by Ludwig Aschoff in 1936 on “Pathology and Biology”, were purely scientific and theoretical and explicitly without any connection to the world of politics. The first post-war meeting did not take place again until 1950 in Munich – with a keynote address by the then Federal President Theodor Heuss.

More than seventy years have passed since then. Is there a defining development in this long period of time that is still noticeable today that you would single out?

Yes, it has to do with the impetuous optimism about progress that characterised the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century and which was problematised in the 1970s at the latest. The Heidelberg medical historian Heinrich Schipperges outlined the new attitude in 1972, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the GDNÄ, in my opinion very aptly: “At the end of the 20th century, we no longer expect that rational social development is coupled with the progress of scientific discoveries and inventions.” However, he added: “We remain convinced that science is still the most reliable instrument for managing progress.”

What is the importance of the GDNÄ today? What function can it assume in the spectrum of science organisations?

The dialogue with the public, which the GDNÄ has always cultivated, is important. In the 19th century, leading naturalists such as the naturalist and natural philosopher Gotthelf Heinrich von Schubert wrote natural science books for school lessons. Today, unfortunately, there is no such thing. In the mid-1990s, an educational commission of the GDNÄ had developed convincing concepts for general science education as, as it put it, “interdisciplinary subject teaching”. However, the implementation in teacher training and everyday school life is still pending. In addition, the GDNÄ as an independent institution is excellently suited to take up central and controversial issues from the natural sciences and medicine for society and culture and to bring them into public discussion. Last but not least, I would like to see it build bridges to the humanities, also to shed light on connections between knowledge of the world and self-knowledge and to address ethical and legal challenges of the present.

One question in conclusion: Today, the term “natural researcher” in the GDNÄ name sounds somewhat antiquated. What did people mean by it two hundred years ago?

If we leave out the natural philosophical dimensions, natural research at that time meant roughly what we understand by natural sciences today. The fact that this term finally prevailed has to do with influences from abroad and the English language. I still consider the term “natural researcher” to be meaningful, attractive and by no means antiquated. In contrast to “natural science” and in agreement with the French “recherche” and English “research”, it emphasises the searching, the questioning, the setting out into the unknown. This is what it is all about, today just as it was when the Society of German Natural Scientists was founded in 1822.

© Institut für Medizingeschichte und Wissenschaftsforschung Lübeck

The science historian Prof. Dr. Dietrich von Engelhardt.

About the person

Dietrich von Engelhardt was born in Göttingen in 1941. He studied philosophy, history and Slavic studies in Tübingen, Munich and Heidelberg, received his doctorate in 1969, worked for several years in criminology and criminal therapy and habilitated in 1976 in the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Medicine at the University of Heidelberg. From 1983 to 2007 he was full professor for the history of medicine and general history of science at the University of Lübeck, and from 2008 to 2011 he was acting director of a comparable Institute at the Technical University of Munich (TUM). Dietrich von Engelhardt took on many other responsibilities, including Prorector of the University of Lübeck (1993 to 1996), President of the Academy for Ethics in Medicine (1998 to 2002), Chairman of the Ethics Committee for Medical Research and the Clinical Ethics Committee of the University of Lübeck (2000 to 2007), and Vice-President of the Regional Committee for Ethics in South Tyrol (2001 to 2010). In 1997 he initiated and organised a symposium in Lübeck on the occasion of the 175th anniversary of the GDNÄ.

Dietrich von Engelhardt has been honoured several times, for example by being admitted to the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina in 1995 and to other national and international scientific academies. He received the Georg Maurer Medal of the TUM Faculty of Medicine in 2004 and the prize of the Zurich Margrit Egnér Foundation, also in 2004. In 2016, he was awarded the Alexander von Humboldt Medal for his research on the history of the GDNÄ.

Dietrich von Engelhardt’s scientific focus areas include: Theory of Medicine; Medical Ethics; Medicine in Modern Literature; 16th Century Botany: Natural Philosophy, Natural Science and Medicine in Idealism and Romanticism; History of Psychiatry; Scientific and Medical Journeys in Modern Times; European Scientific Relations; Dealing with Illness by the Sick; Bibliotherapy; Biographies and Pathographies of Natural Scientists, Physicians and Artists.

Further links:

Bücher (Ed. Dietrich von Engelhardt)

© G. C. Wilder / Stadtmuseum Fembo-Haus, Nürnberg

On the occasion of the 23rd meeting of the „Gentlemen Natural Scientists and Physicians” in 1845, the city of Nuremberg invited to a banquet in the town hall.