“Once again, Mr Privy Councillor prefers not to come”

He looked after the GDNÄ’s heritage for three decades, now he is retiring: Head of Archives Wilhelm Füßl on precious documents, pitfalls of copyright law and his long struggle to get historical originals returned.

Dr Füßl, the Deutsches Museum looks after numerous archives of scientific institutions, including the archive of the GDNÄ. What is its significance?

It is of great national importance. The GDNÄ is not only the oldest interdisciplinary scientific society in Germany, it is also the mother of many specialist societies such as the German Physical Society. Another peculiarity: many archives of scientific institutions were completely destroyed during the Second World War, but at least some historical holdings of the GDNÄ have been preserved.

What are the oldest documents?

These are the reports and negotiations of the GDNÄ meetings. However, some only exist as copies in our archives.

Do you have a favourite item in there?

I find the account book from 1911 particularly interesting, for example, according to which an archivist was paid a meagre 72 Reichsmarks; today that would correspond to a purchasing power of around 300 euros. What I also like to look at is the diary of 15-year-old Ulrike Schwartzkopff, who accompanied her father to the assembly in Weimar in 1964 and recorded her impressions and thoughts in a very lively, differentiated and pleasant way. Or a microfilm on the organisation of the Berlin Assembly, where there is a marginal note by Alexander von Humboldt on a letter from 1828: “Herr Geheimrat pflegt wieder nicht zu kommen” (approx.: “Once again, Mr Privy Councillor prefers not to come.”). Goethe was meant.

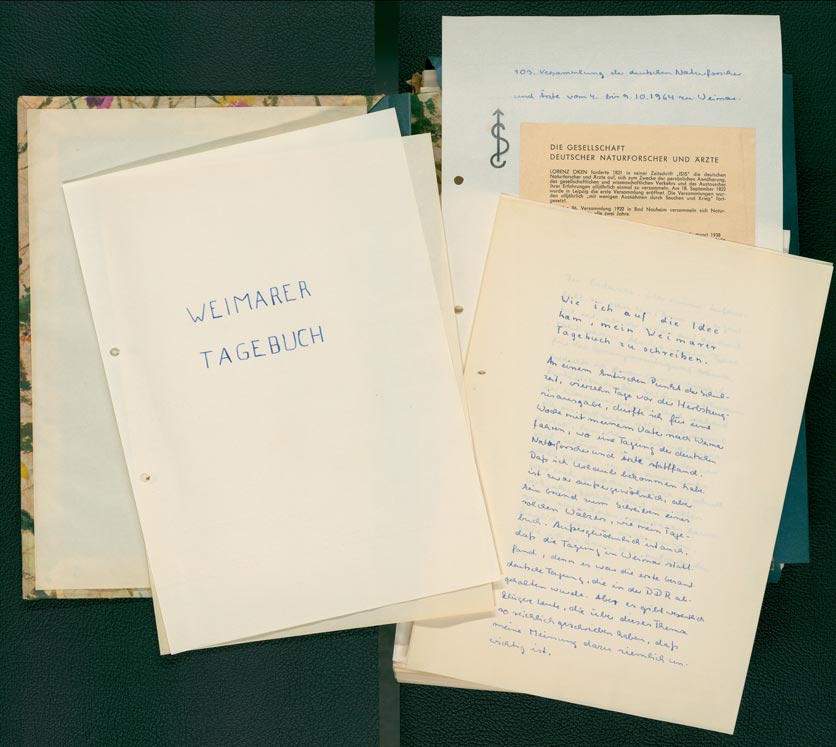

Diary of the 15-year-old schoolgirl Ulrike Schwartzkopff from the meeting of the 103rd Assembly of the GDNÄ in Weimar 1964.

How can we imagine the GDNÄ archive as a whole?

They are mainly conference proceedings with reports of meetings, lecture manuscripts, annual reports of the board, files of the office and several hundred photographs. Most of the archive material dates from the period after 1945, with density increasing strongly from 1960 onwards. Older holdings were confiscated by Soviet troops at the end of the war and transported to Moscow. They have been lost to this day. The remaining old files from the 19th and early 20th centuries were privately owned by board members or were acquired by us. The majority of these documents date from the years 1893 to 1921.

Where can you find the archive in the Deutsches Museum?

It is housed on the top floor of the library building. The GDNÄ archive now covers an impressive 23 shelf metres, making it one of our largest institutional archives. The reading room is only a few metres away from the stacks, and ordered documents are brought in quickly. So it’s worth the trip even for visitors in a hurry.

How great is the interest in the GDNÄ archives?

In the last twenty years, more than 500 files have been borrowed. That is a considerable number, also compared to the use of similar archives in the Deutsches Museum.

Do you know more about the users?

I know from conversations that many of them are academics. But that is by no means a prerequisite. Anyone interested is welcome and can read the holdings free of charge or take pictures with their digital camera for private purposes.

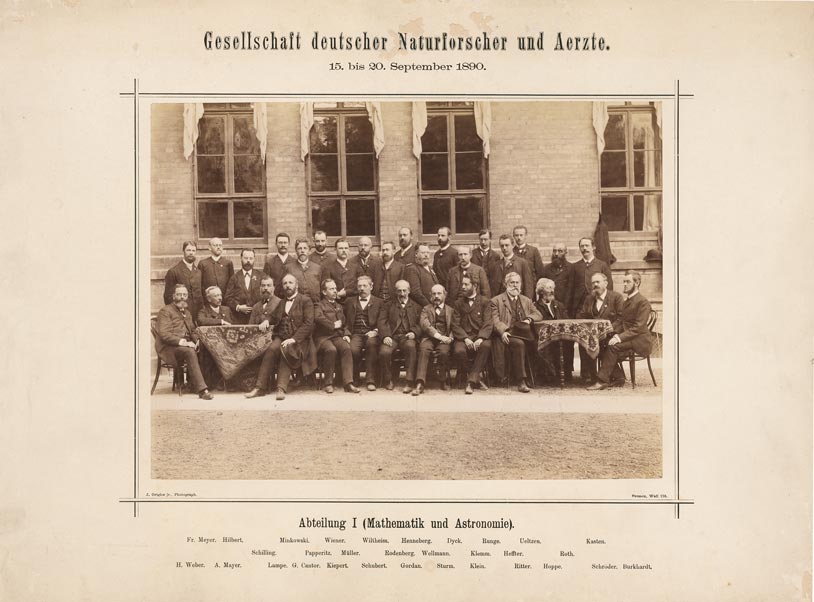

Mathematicians in a group picture on the occasion of the GDNÄ meeting in 1890.

That sounds a bit cumbersome. Aren’t the documents also available online?

We would like to get there, but copyright law is the main obstacle. Without the express permission of the author – a speaker at a GDNÄ meeting, for example, or his or her descendants – the work may not be freely used until seventy years after his or her death. For us, this means that unless there is a declaration of consent, and this is rarely the case with older documents, we may only publish lectures, letters or reports if they date from before 1885. Looking to the future, this could mean the following for a lecture given by a 40-year-old female researcher at the 2022 anniversary conference in Leipzig: If the researcher turns 90, her beautiful speech may not be distributed without conditions until 2142 at the earliest. That is, of course, a joke.

Is there a pragmatic solution?

Hardly in the case of more recent documents. Older publications could be used via the online services of other libraries. As soon as a document is on the internet, you can refer to it. So it would be conceivable to put a list of links to such sources on the net – and that is exactly what is being considered at the moment.

So your work clearly goes beyond the quick retrieval of documents. What does it all involve?

Oh, there’s a lot that goes into it. Let’s take the GDNÄ archive as an example. It arrived here in 1989, three years before I took up my post, and comprised 13 shelf metres at that time. In 2001, another ten shelf metres were added. Such a collection first has to be professionally organised and systematically linked with other collections. One result are finding aid books with an extensive table of contents and many keywords that lead to potentially relevant information in the entire archive material. Then there is material on the GNDÄ in many other holdings of our archive. For example, anyone researching the physicist Walther Gerlach and going through his estate will find references to lectures given by GDNÄ member Gerlach in the 1950s – not only in the finding aid book, but also in conversation with us. In addition, we maintain contact with institutes of the history of science throughout Germany and encourage research on our holdings. In this way, for example, a dissertation on the work of the GDNÄ between 1822 and 1913 was written at the University of Würzburg. And, very importantly, we regularly browse through scholarly antiquarian bookshops and auction catalogues in order to be able to fill gaps in our holdings.

The packed GDNÄ archive before it was transported to the Soviet Union (around 1945)

How far have you got with the GDNÄ archive?

Some things could be bought, but we could not compensate for the great loss of historical files. We know that the GDNÄ archive was at its original location in the Karl Sudhoff Institute in Leipzig until shortly before the end of the war, when it was moved to nearby Mutzschen Castle for protection. But that was of no use: in 1945 the Soviets confiscated a total of 53 boxes and one roll with archive numbers 34 to 86 and took them out of the country. I have been on the case since 1992 and have tried everything possible through political, academic and personal channels. The hope was to at least get microfilms of the GDNÄ holdings. At first there was no response. Later, Moscow cunningly said that the archive had been returned to the German Society for Naturopathy. It went on like that for decades. I am sure that the archives of the GDNÄ were not destroyed – they are probably stored in a Russian museum somewhere. I guess we’ll have to wait for a political thaw to make any progress on the matter.

Does the lost archive also contain documents from the Nazi era?

I assume so. In any case, we don’t have a single original document from those years.

You mentioned the 1964 meeting in Weimar – the first and only GDNÄ event in the GDR. Do you know more about it?

Normally we do not include mass files in our archives, for example business correspondence with members or lists of participants at meetings. We made an exception for the GDR period at the GDNÄ. We know that the conference proceedings were distributed via the Leopoldina in East Germany and were in great demand until the fall of the Wall, even though many East German members had left the GDNÄ in 1949. To work through all this would be a highly interesting contribution to research.

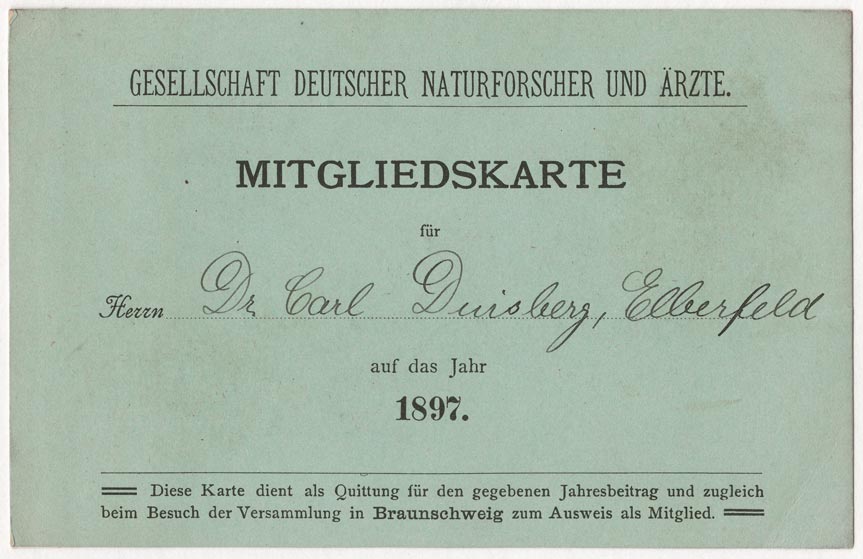

Membership card of the GDNÄ for the important chemist and industrialist Carl Duisberg.

You will have more time soon…

That’s right. I retire at the end of May and hand over the reins to my deputy, the historian Dr. Matthias Röschner. But the scientific history of the GDR is not my metier; others are called upon to do that. I will remain true to my themes and already have a few book projects in mind.

For example?

A biography of the engineer Arthur Schönberg. He was the first employee of the founder of the Deutsches Museum, Oskar von Miller. I published a biography about von Miller in 2005. Arthur Schönberg, who died in the Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1943, is commemorated today by a plaque in the Deutsches Museum.

Is a visit to the 2022 GDNÄ Assembly in Leipzig also on your agenda?

I have been to most of the meetings since 1992 and have heard very exciting lectures. One in particular stuck in my mind, it was about the expansion of the universe. What I also enjoyed were the meetings with great scientists. So, yes, I think I will be there in Leipzig.

Meagre pay in 1912: two archivists earn 71.85 marks.

About the person

Dr. Wilhelm Füßl was born in 1955 in the Upper Palatinate. He studied history, German language and literature and social sciences at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich and received his doctorate there in 1986 with a thesis on the legal philosopher Friedrich Julius Stahl. After working in Germany and abroad, he moved to the Deutsches Museum in Munich in 1991. In 1992 he took over as head of the archive. In this capacity, Wilhelm Füßl is a co-opted member of the Board of the GDNÄ until his retirement in May 2021 – a post that Dr Matthias Röschner will take over as the new Head of the Archives.

Dr Füßl’s research interests include the history of technical collections and the interactions between biographies and the history of science and technology. His most important works include the books “Geschichte des Deutschen Museums. Actors, Artefacts, Exhibitions” (2003) and, published in 2005, “Oskar von Miller (1855-1934). A Biography”. Some of his books have been awarded prizes. Wilhelm Füßl conceived several exhibitions, including a show on the history of the Deutsches Museum, which is on permanent display.

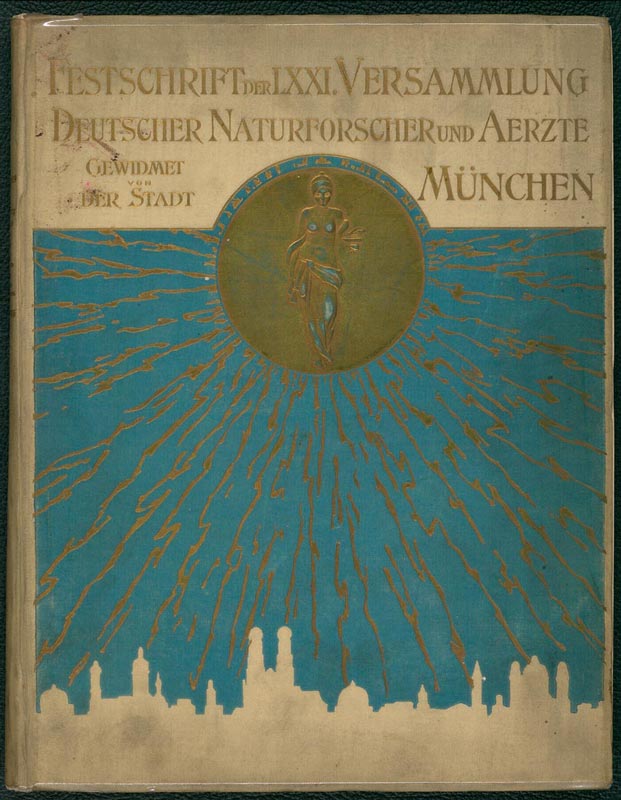

Cover of the Festschrift on the occasion of the Assembly in Munich in 1899.

The archive of the Deutsches Museum is one of the world’s leading special archives on the history of science and technology. On 4.7 shelf kilometres in the library building on Munich’s Museum Island, bequests of important scientists and researchers, manuscripts and documents, plans and technical drawings, extensive archives of companies and scientific institutions as well as more than one million photographs are stored and prepared for research. The archive is open to anyone interested in the history of technology and science. Use is free of charge.

View into a storage room of the archive of the Deutsches Museum.

Further information:

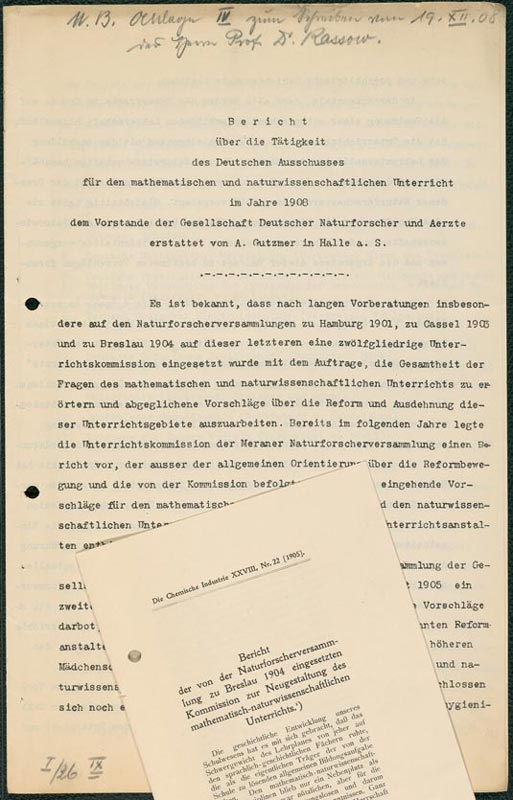

As early as 1900, the GDNÄ was committed to school youth. Here is a document on the subject of “teaching reform”.

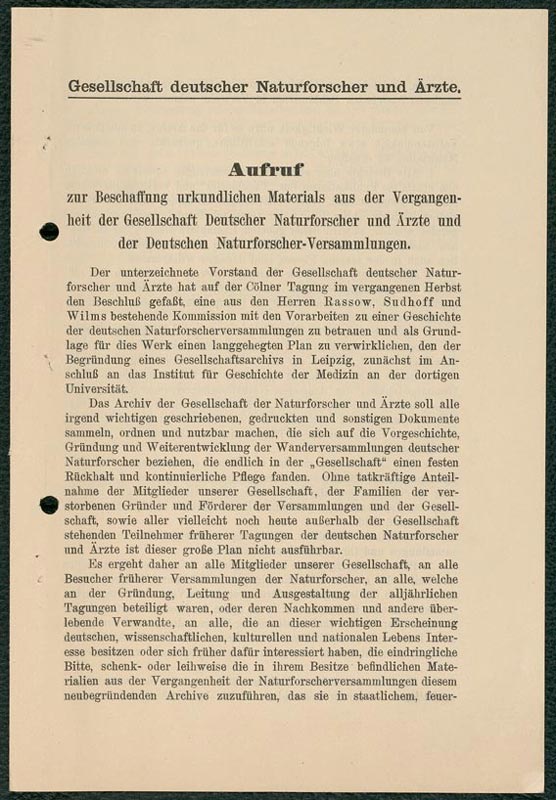

Call for the collection of historical documents on the GDNÄ, ca. 1921.

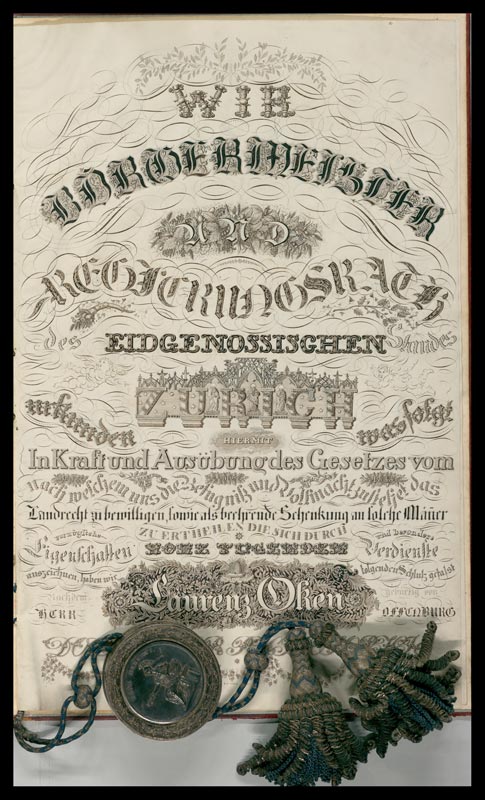

Citizenship certificate for the founder of the GDNÄ, Lorenz Oken, from 1835.