“Nothing could scare me after that”

BSE, bird flu, coronavirus: how the renowned virologist Thomas Mettenleiter has contributed to overcoming major epidemics, what has kept him on the Baltic Sea island of Riems for 27 years and what his audience can expect at the GDNÄ Assembly 2024.

Professor Mettenleiter, as President of the Friedrich Loeffler Institute, Federal Research Institute for Animal Health, for many years, you had to deal with world-shattering epidemics, just think of the BSE crisis, bird flu and the coronavirus pandemic. Which was the biggest challenge?

For me personally, it was definitely the BSE crisis. After that, nothing could scare me. I was still relatively new in office when the first cattle born and raised in Germany tested positive at the end of November 2000. The excitement was huge. At the time, we knew very little about the prions that caused the disease, but we were expected to provide competent information as soon as possible. Some time earlier, an informal expert commission had been set up under my chairmanship. In April 2000, we recommended that the Federal Government should prepare for the first case of indigenous BSE. Unfortunately, this did not happen.

Nevertheless, the BSE crisis was ended quickly. How did this succeed?

The decisive factors were the ban imposed at EU level on the feeding of animal meal, for example, the removal of risk material from the food chain and the extensive testing of slaughtered cattle depending on their age. The number of cases then fell rapidly. As far as we know, only two animals born in March and May 2001 were still infected in Germany. It was an extremely turbulent time, during which two federal ministers, Andrea Fischer and Karl-Heinz Funke, resigned. During these years, I learnt how important communication between science, politics and the media is. Fortunately, the measures proposed by the scientific community were quickly implemented and proved successful. In this respect, the BSE crisis is a successful example of science-based disease control

© Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut

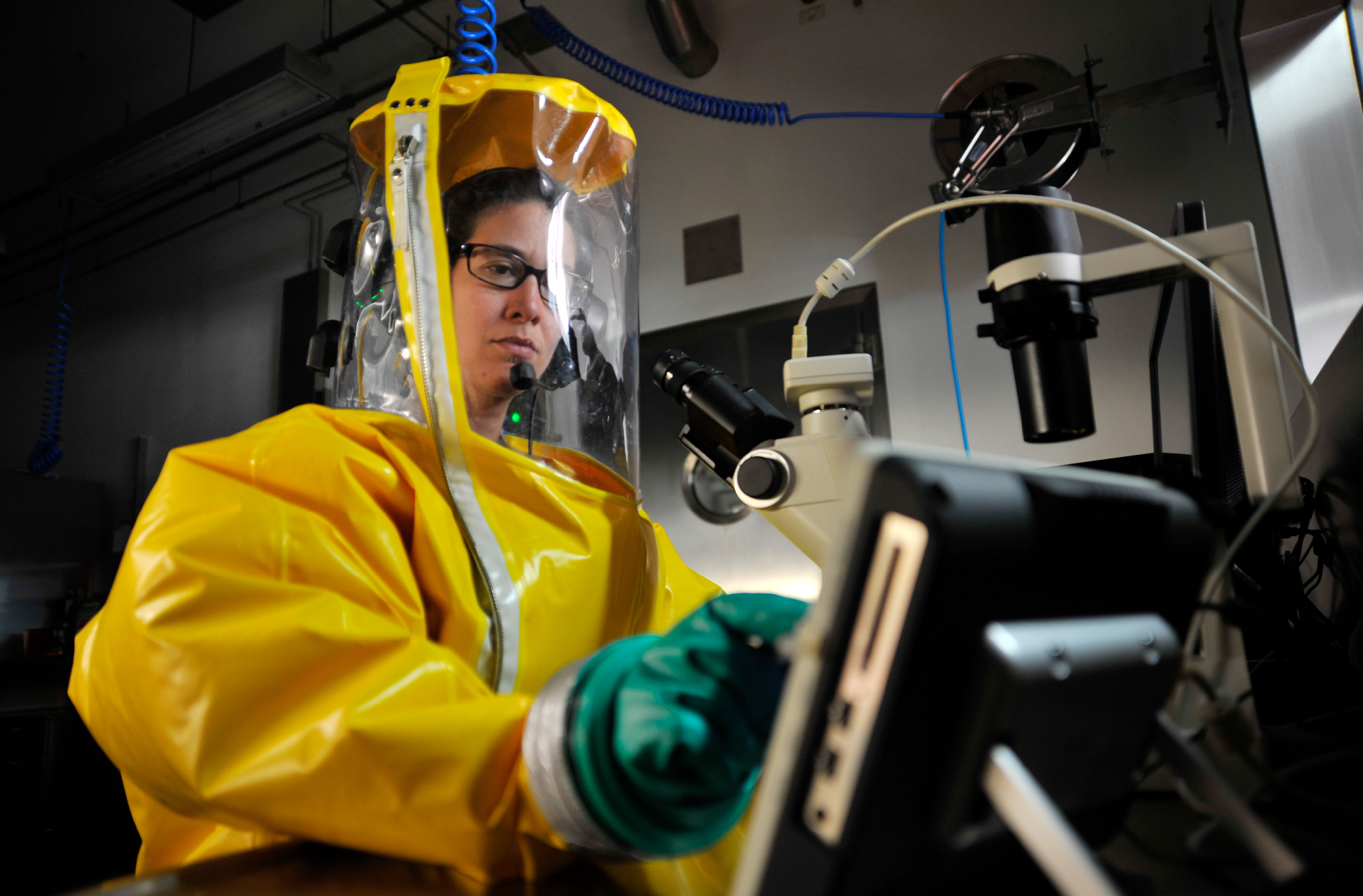

A scientist works in a full protective suit in the laboratory of the highest biosafety level 4 zoonoses. This is where research is conducted into pathogens such as Ebola and Nipah viruses. The suit is connected to the air supply via a valve, which constantly supplies air. This also inflates the suit so that even if there was a small hole, nothing would get inside via the escaping air flow. The scientist checks cell cultures on a screen.

How much was your expertise in demand during the coronavirus pandemic?

During the three COVID-19 years, other institutes were at the centre of political and media attention. However, we at the FLI were asked essential questions right at the beginning of the pandemic: Are farm animals in Germany susceptible to SARS-CoV-2? Does this jeopardise our food supply and do they represent a potential reservoir? Thanks to our modern research infrastructure on the island of Riems with high-security isolation stables, we were able to immediately test whether cattle, pigs and chickens, for example, are susceptible to the pathogen. We also investigated the interaction of the pathogen with other animals such as mice, golden hamsters, fruit bats, ferrets and raccoon dogs in order to find and characterise possible reservoirs or models for human infection.

What did you find out?

Cattle, pigs and chickens were not or only very slightly infectious and did not pass on the pathogen. In this respect, there was neither a risk in terms of food supply nor with regard to the creation of a new reservoir. Fruit bats, ferrets and raccoon dogs, on the other hand, proved to be susceptible to the pathogen, but did not fall ill and were still able to pass on the pathogen efficiently. This fits in with what we know about reservoir animals and bridge hosts. Hamsters and special genetically modified mice became severely ill. Ferrets, in particular, reproduced the largely mild human infection affecting only the upper respiratory tract, while golden hamsters and these mice showed the clinical picture of severe COVID-19.

There is currently much discussion about the need to come to terms with the coronavirus crisis. What do you think?

We should definitely analyse what happened objectively in order to learn from it for the future. Many decisions had to be made quickly and under uncertain conditions, especially during the hot phase – this should always be taken into account. A uniform policy for the whole country is important for the future; we should avoid a federal patchwork quilt in situations like this. However, the coronavirus years have also shown how immensely important basic research and modern research infrastructures are. We have them to thank for the highly effective mRNA vaccines, which had been researched for a long time, as well as numerous findings that helped us to survive the crisis. In order for this to continue in the future, sufficient funding is needed – not only for the establishment, but also for the maintenance of research facilities, personnel and training.

It is often said that the next pandemic is sure to come. What are the new threats?

We are currently in an inter-pandemic phase, that much is clear. But no one can say exactly where the dangers are coming from. What we do know is that three quarters of new human infections come from the animal kingdom and that pathogens such as the coronavirus continue to jump back and forth between animals and humans. We must never lose sight of influenza viruses: they are highly variable and adapt quickly to new circumstances. Fortunately, there is a global monitoring system for influenza viruses under the aegis of the World Health Organisation (WHO). We also need something similar to monitor animal populations in order to detect pandemic risks quickly. An international agreement on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response could help here. This is currently being negotiated under the leadership of the WHO and I am still cautiously optimistic that the member states will be able to agree on this. This would also be very much in line with the One Health concept, which is becoming increasingly popular and which sees humans as part of the animal kingdom in a shared environment.

The type of animal husbandry, which is also the focus of the Friedrich Loeffler Institute, plays an important role here. What trends do you see in this area?

The view is changing and animal welfare is becoming more important. In livestock farming, quality is becoming more important than quantity. To what extent and over what period of time this happens is also a question of funding and ultimately a political decision. This also applies to another issue: the silent pandemic of antibiotic resistance. It is favoured by the excessive use of antibiotics in all areas. In Germany, their use to promote growth in animal husbandry is banned, but this practice is still common in many countries. However, it is not just about animals; the use of antibiotics in humans must also be more targeted and more restrained.

© Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut

The Friedrich Loeffler Institute (FLI) has two animal barn units with biosafety level 4 zoonoses, where full protective suits are also mandatory. In Europe, only the FLI currently has such animal houses; there are a handful worldwide, for example in Canada and Australia.

You went to East Germany as a West German professor during the reunification period – and stayed there. What experiences did you have?

Initially, I was met with an interested distance, but also with curiosity and high expectations. The distance had to do with the fact that, unlike the institute directors before me, I am not a veterinarian, but a biologist. In addition, I was still quite young when I came to the island of Riems with my Tübingen working group in 1994. In the wake of reunification, the institutes had shrunk from 850 to 162 employees. The infrastructure was dilapidated. In my perhaps somewhat youthful recklessness, this did not deter me, but rather challenged me. What helped me a lot were the many motivated colleagues at all levels of the institute, who had a lot of expertise and experience. It has been a long journey, but today the Institute plays in the Champions League of the field, both academically and in terms of infrastructure. Its development is certainly one of the East German success stories, as described by my Greifswald colleagues Michael Hecker and Bärbel Friedrich in their book and in the interview on this website. For me, the Institute is a life’s work and I am happy to have been given the privilege of continuing the tradition of the co-discoverer of the virus, Friedrich Loeffler.

Your major research topic, animal viruses, has occupied you for a long time. How did you come across the topic?

The trigger was Hoimar v. Ditfurth’s history of evolution “In the beginning was hydrogen”. My parents gave me the book as a present in 1972 and I read it with great enthusiasm. I was particularly fascinated by an illustration depicting bacteriophages, i.e. viruses that infect bacteria. That was the seed for my career – and I am still an enthusiastic virologist.

That doesn’t sound like retirement, which you have officially been in for almost a year.

That’s right, I’m still very busy, even if I no longer spend up to 14 hours a week at the institute. But all in all, I have almost a full-time job again and sometimes I wonder how I used to do it on the side, so to speak. A new experience for me is giving talks to students about virology and One Health, for example last year in Göttingen and in the next few weeks in Greifswald and in Sigmaringen in Upper Swabia, my old home. I chair a working group on One Health at the Hamburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities and I chair the veterinary medicine section of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. As a scientific advisor, I support several UN organisations and the World Organisation for Animal Health in the One Health High-Level Expert Panel. I also continue to teach at universities and give lectures on my core topics.

At the GDNÄ Assembly 2024 in Potsdam, you will be giving a lecture on climate change and infectious diseases. Can you give us a few details?

I will be presenting the One Health concept in more detail, including its history, because it is by no means brand new. It will also be about pathogens, especially viruses, which are spreading as a result of climate change. We will be talking about so-called vectors, i.e. carriers of infections such as mosquitoes and ticks, which are influenced by climatic changes. The whole development has an uncanny dynamic and I try to visualise this.

© Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut

About the person

Thomas Christoph Mettenleiter is a virologist and molecular biologist. He studied biology in Tübingen from 1977 to 1982 and wrote his doctoral thesis on herpes viruses in pigs. After a research stay in Nashville, USA, he habilitated in virology at the University of Tübingen. After reunification, he went to the Friedrich Loeffler Institute, Federal Research Institute for Animal Health (FLI) on the island of Riems. There he headed the Institute of Molecular Virology and Cell Biology from 1994 to 2019. In 1996, he took over the management of the entire FLI. In 1997, he was appointed adjunct professor at the University of Greifswald and in 2019 honorary professor at the University of Rostock. After 27 years as President, he retired in June 2023.

Mettenleiter’s field of research is viral infections in livestock. His work contributed significantly to the first development of genetically modified live vaccines and to the effective control and eradication of a highly contagious viral disease, Aujeszky’s disease, in pigs.

Thomas C. Mettenleiter has been honoured many times for his achievements. He is a member of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina, the Academy of Sciences in Hamburg, the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Royal Belgian Academy of Medicine. For his work in the field of animal disease research, he was awarded the Gold Medal of the World Organisation for Animal Health WOAH in May 2023 and the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in January 2024.

© Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut

About the FLI

The Friedrich Loeffler Institute, Federal Research Institute for Animal Health (FLI), is an independent higher federal authority within the portfolio of the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture. In addition to the headquarters on the island of Riems in the Greifswald Bodden, there are four other locations in Braunschweig, Celle, Jena and Mariensee/Mecklenhorst. A total of twelve specialised institutes with around 800 employees are dedicated to both basic and practice-oriented topics.

Their work centres on the health and welfare of farm animals and the protection of humans from zoonoses, i.e. infections that can be transmitted between animals and humans. To this end, the FLI develops methods for better and faster diagnosis as well as the basis for modern prevention and control strategies. To improve the welfare of farm animals and in the interest of high-quality food of animal origin, animal welfare-orientated husbandry systems are designed and tested at the FLI. Important goals are the preservation of genetic diversity in farm animals and the efficient utilisation of feedstuffs.