“Let us encourage young people to follow seemingly crazy ideas”

Why Stuart Parkin, Director at the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics, gave up his top job in California, how he is giving data processing a leg up and what future he sees for Germany.

Professor Parkin, a few years ago you were still at IBM in Silicon Valley, now you work in Halle an der Saale. Was that a good swap?

I think so, even though the two stations are very different. However, they are similar in one respect, which is very important to me, and that is scientific freedom. I had that as research director at IBM and here at the Max Planck Institute for Microstructure Physics in Halle I can also determine my own course.

And yet it’s a big leap you’ve made: from industrial research to a publicly funded institute, from California to Saxony-Anhalt. What made you do it?

My love for my wife Claudia Felser. We met at Stanford and decided to move to Germany together a few years ago. She is a chemistry professor and director at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids in Dresden. We are not far from our home to our institutes. Not only do we share a fascination for new materials, we also work together on projects.

© Max Planck Institut fuer Mikrostrukturphysik

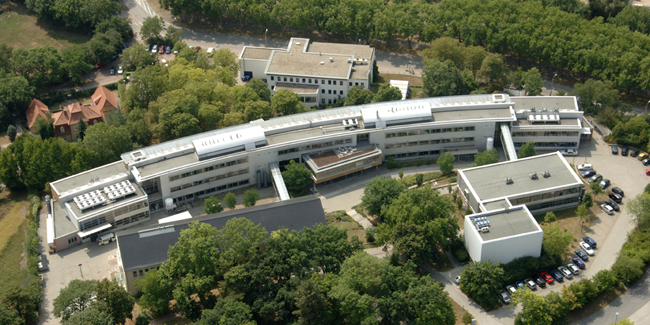

The Max Planck Institute for Microstructure Physics was founded in 1992 as the first institute of the Max Planck Society in East Germany. The research focus is on novel materials with useful functionalities. Today, the institute offers space for around 150 employees.

What exactly is your research about?

To put it in a nutshell: I create completely new materials for information processing. They are needed because we are at the end of the silicon age and urgently need basic materials for a faster, more efficient data world. Our materials consist of wafer-thin magnetic layers. They make it possible to use the magnetic moment of the electron to store and process digital data, and not just its electrical charge, as used to be the case in semiconductor electronics. Spintronics is the corresponding technical term. I have dedicated most of my professional life to it and during this time I was able to make a significant contribution to the fact that magnetic drives are standard today. But that is only part of the story.

How does it continue?

One important spintronics application is the spin valves I invented. These are thin-film read heads that can detect very small magnetic domains on hard drives and significantly increase their storage capacity. More than ten years ago, the so-called Racetrack memory was developed under my leadership. This technology, based on magnetoelectronics, processes digital information a million times faster than conventional hard disks. Currently, together with my wife, I am researching skyrmions and antiskyrmions, i.e. nanometre-sized magnetic objects that could pave the way for ultra-fast and at the same time power-saving data processing in the future. Our results have been published in high-ranking journals, most recently in Nature.

When it comes to efficient information processing, the human brain is unrivalled. Do you draw inspiration from it?

Of course I do. I already started my first studies at IBM and we are also working in this extremely exciting field in Halle. We want to understand how the brain manages to trigger material reactions by means of tiny ionic currents. That is electrochemistry at its finest. Our goal is to mimic the incredibly economical and precise way the brain works. This cannot be achieved in the short term, you need staying power.

What can be achieved in the next few years?

For me, it’s about accelerating the invention of new materials. That’s why I completely rebuilt the institute in Halle and received excellent support from the state of Saxony-Anhalt, the Max Planck Society and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Today we work here in a large team of physicists, chemists and biologists – to name just a few disciplines. We have state-of-the-art imaging technology at our disposal and a new clean room in which we can produce the finest nanostructures. Most of it we built ourselves, you can’t buy something like that on the market.

© burckhardt+partner

New research building for the chip technology of tomorrow (virtual view): With an investment of 50 million euros, the Max Planck Institute for Microstructure Physics in Halle is being expanded with modern laboratories and offices. The new building with a floor space of 5,500 square metres is scheduled for completion by the end of 2024. The institute will then be able to accommodate up to 300 employees.

Your research should be of great interest to industry?

That’s right. There are collaborations with the Korean IT company Samsung, for example. Other companies are also keeping a close eye on what we are doing. Among them is the American chip manufacturer Intel, which recently announced billions in investments in Europe.

How do you rate the general conditions for your research in Germany?

We have really good conditions. A big plus is that Germany invests a lot in basic research, much more than other countries in Europe. There are excellent specialists in the country and ambitious young people with good ideas.

Where do you see Germany in international comparison?

There is still some catching up to do. Let’s take the example of the USA: there, digitalisation has really arrived in the middle of society, but I don’t see it that way in Germany yet. The powerful and rich companies in Silicon Valley can pay professionals high salaries, and we often can’t keep up. Moreover, many patent rights are in the USA – that also makes competition more difficult. The pandemic has shown how big the differences are between countries. All of a sudden, video conferencing was en vogue and US providers like Zoom or MS Teams were at the forefront. Why, I ask myself, is a German company like SAP not playing along? The prerequisites are certainly there.

How can Germany make up ground?

The best way is to invest in young people. We should encourage them to follow even seemingly crazy ideas and take risks. At universities, people should be able to learn how innovation works and how to compete successfully. Some Asian countries designate certain zones where company founders do not have to pay taxes for ten years. This could also be a model for us, especially in eastern Germany, where there are still many vacant areas.

The federal elections are just behind us, the coalition negotiations are underway. What do you expect from the next federal government in your field?

A strong push for digitalisation. As the leading economy, Germany should lead the way in this area and help Europe speak with one voice. That would be important in order to survive in international competition and to enforce important values such as data security.

You are involved in numerous professional societies. How important is your work in the GDNÄ for you?

I am a European and would like to contribute to making our continent more competitive. The GDNÄ can play an important role in this, for example by supporting young people. But also by inviting controversial, cultivated discussions about current scientific topics. I know this from Great Britain and would like to see more public debate of this kind in this country as well. It could be a good remedy for the increasing scepticism about science in society.

© Sven Doering

© Sven Doering

Stuart S. P. Parkin

About the person

Stuart S. P. Parkin was born in Watford, England, in 1955. After completing his doctorate in solid-state physics at the University of Cambridge, he joined IBM as a postdoctoral researcher, where he was made a Fellow in 1999, the company’s highest technical award. Between 2004 and 2006, he conducted research at the Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule (RWTH) Aachen University with a Humboldt Research Award. Professor Parkin headed the IBM Almaden Research Center in San Jose, and was director of the Spintronic Science and Applications Center (SpinAps), founded in 2004. He was also a professor at Stanford University. He is a member of numerous international academies such as the Royal Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and has received numerous awards, most recently the King Faisal Prize 2021 worth 200,000 dollars. The physicist with three citizenships in the UK, USA and Germany has published around 400 scientific papers and holds more than 90 patents. Since 2014, he has been director at the MPI for Microstructure Physics Halle and Alexander von Humboldt Professor at the Institute of Physics at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. Shortly afterwards, Stuart Parkin joined the GDNÄ and was elected subject representative for engineering sciences.

Further Information: