“There are bumpy years ahead”

Marion Merklein, engineering scientist, company director and member of the GDNÄ Board, on turning points in mechanical engineering, taster courses and early successes with the hammer drill.

Professor Merklein, at your institute at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, you develop entire production lines and realise them together with industrial companies. Are the prospects for German mechanical engineering really as bleak as is often said at the moment?

I’m not one of the pessimists. But there will be a lot of rumbling in the country over the next few years. Mechanical engineering is in the midst of a major transformation that will probably keep us busy until the end of the decade. Only then will things start to pick up again.

What transformation are we dealing with in mechanical engineering?

The pivotal point is the energy transition, which will lead us away from fossil fuels and towards green electricity and hydrogen. At the same time, energy consumption and waste volumes are to be reduced. These alone are colossal challenges for the automotive industry and many other sectors of mechanical engineering. The situation is further exacerbated by the declining order situation against the backdrop of a global economic downturn and a dramatic shortage of skilled labour. We must not underestimate the problem from a social perspective, as one in five jobs in Germany depends on mechanical engineering.

How does your research contribute to solving these problems?

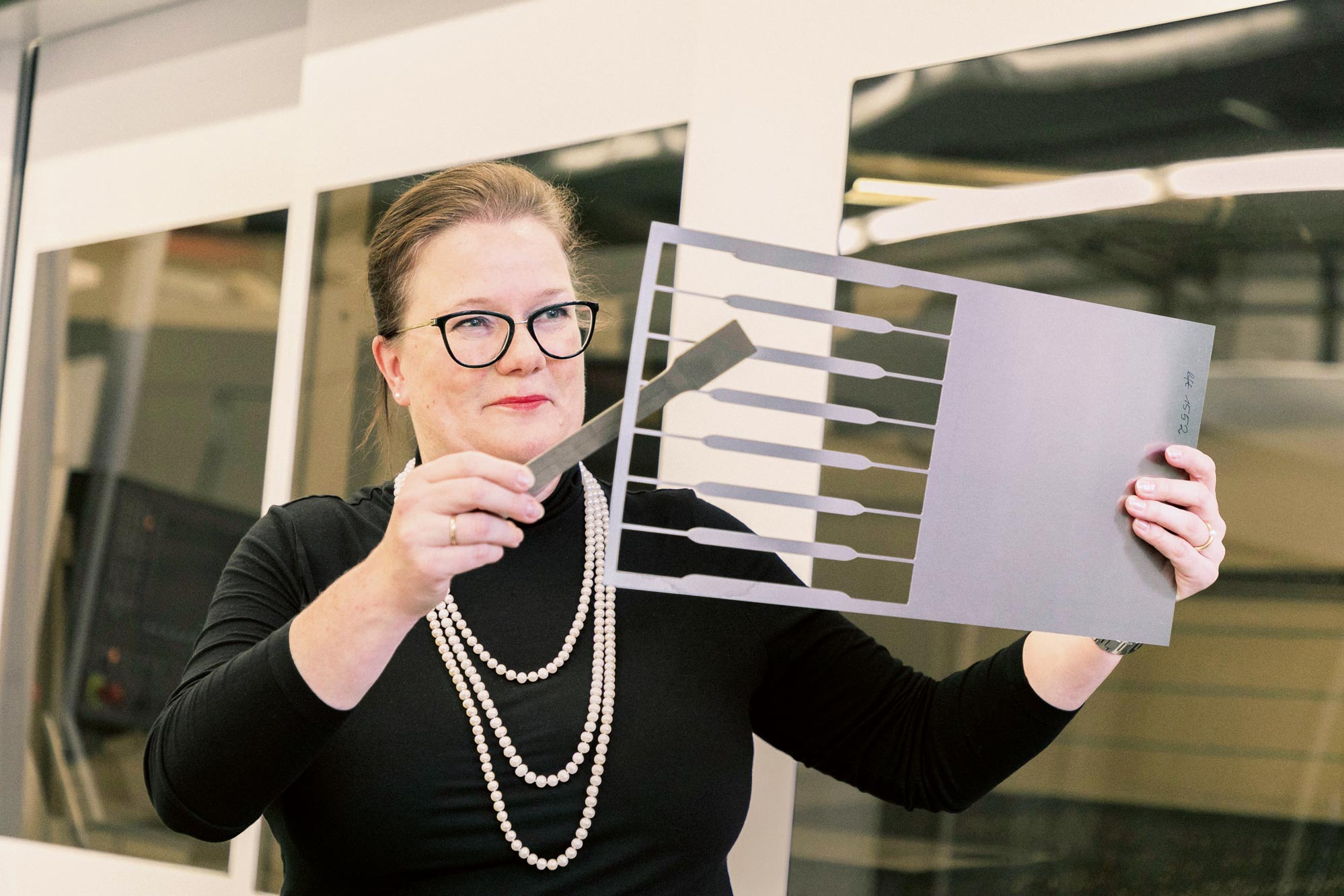

At our university institute, a lot of research centres on the question of how to streamline process chains. For example, in the construction of hydrogen engines. Today, such engines are practically manufactory products with small series such as the °Mirai°: Toyota only produces 30,000 of these saloon cars with fuel cells per year. This is of course uneconomical in the long term. We are therefore currently designing production lines for large-scale production. The aim is to be able to produce millions of hydrogen drives for motor vehicles of all kinds in the future. We are also developing techniques to reduce heat consumption when joining components and chipless cutting techniques, which leads to less waste when cutting workpieces, for example.

In addition to your work at the university, you are also the head of a company. What drives you?

We want to put research results from the university into practice faster than usual. That’s why I took over the management of the company “Neue Materialien Fürth” in 2019. This is a state research institution, 51 per cent of which is owned by the Free State of Bavaria and 49 per cent by several co-owners. I also own a share. The company can be compared to a Fraunhofer Institute, but with a much leaner administration. We have large industrial-scale facilities at our disposal. This enables us to carry out realistic experiments that are not possible at the university.

© FAU/Giulia Iannicelli

Are there already tangible results?

Yes, there are, and something will soon be added that will advance electrical engineering. It’s about an internal component that I can’t reveal any more about now because the patent process is still ongoing. The development is based on the results of a Transregio funding programme on sheet metal forming and is a good example of successful research transfer. Neue Materialien Fürth also carries out contract research and provides services – the bottom line is that we are in the black.

Women are still a minority in mechanical engineering. What is the situation like in your environment?

When I took up my professorship, I was the only woman in the field far and wide. But a lot has happened over the years. Today, almost a third of professorships in mechanical engineering at FAU are held by women. I definitely see myself as a role model. And in my working groups, I realise time and again that mixed teams achieve the best results.

Where does your fascination for the profession come from?

My father played a big role. I was eight years old when he put a Hilti in my hand to make a wall breakthrough. I really wanted to do it, he trusted me to do it and I managed it. I was very good at physics at school and when it came to studying, I decided in favour of materials science. As time went on, I liked mechanical engineering even better, I switched and did my doctorate in this subject.

© FAU

You quickly made a career for yourself and were already a professor at the age of 34. What gave you wings?

Above all, the reliable support of my doctoral supervisor and mentor, Professor Manfred Geiger. He encouraged me right from the start and took me along to all kinds of events and conferences. This allowed me to grow into management positions.

Today, it is up to you to promote the next generation.

Unfortunately, young talent is rare. Compared to pre-pandemic times, we have up to 40 per cent fewer students and correspondingly fewer young academics. Technical science degree programmes have lost their appeal for young people. If they go in a technical direction at all, many of them tend to do vocational training. Foreign students can only partially compensate for this deficit. We therefore have to come up with something to get young people interested in our subject.

What are you doing to achieve this?

My team and I give talks in schools, offer technology internships and, during the Whitsun holidays, we organise a taster university where students can look over our shoulders for a week. We are currently working on experiments suitable for small children, which we can also take to daycare centres.

You are a representative for engineering sciences in the GDNÄ. What motivated you to take on this role?

I was asked very kindly by the Executive Board and considered the offer an honour. I like the interdisciplinary nature of the GDNÄ, that’s what makes it so special for me and I’m happy to get involved.

© FAU

About the person

Prof Dr Marion Merklein’s research career is closely linked to the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU). There she studied materials science and obtained her doctorate, where she worked as a senior engineer and research group leader and completed her habilitation. At the age of just 34, Merklein received three offers for professorships from Germany and abroad, but once again decided in favour of FAU. Her Chair of Production Engineering is regarded as one of the leading international centres in its field with excellent contacts in science and industry.

Marion Merklein’s more than 600 research papers cover a wide range of topics, with her main interests being the design and optimisation of lightweight sheet metal constructions, hot sheet metal forming (press hardening) and sheet metal forming. In many cases, Merklein succeeds in bridging the gap between materials science and production technology, often addressing issues relevant to industrial applications.

The 50-year-old scientist has received numerous awards, including the Leibniz Prize of the German Research Foundation (2013) and the Bavarian Order of Merit (2018). She is a member of the National Academy of Sciences Leopodina, the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities and the German Academy of Science and Engineering acatech. Marion Merklein also heads a company, Neue Materialien Fürth GmbH, a state research organisation that aims to transfer the findings of basic scientific work to industry.