Martin Lohse Exciting times for science

“Exciting times for science”

Professor Lohse, the GDNÄ will be 200 years old in September 2022. How will this anniversary be celebrated?

200 years: this is really a significant and wonderful anniversary. During these 200 years science has developed in an incredible way, all over the world, but particularly in Germany – and often from within the GDNÄ. We want to celebrate this special anniversary with a very special four-day anniversary conference in September: in the city where the GDNÄ was founded, Leipzig, and in the beautifully modernised Art Deco Congress Hall at the Leipzig Zoo.

Who is invited to this celebratory conference?

All members are cordially invited, plus participants in the student programme and former scholarship holders, as well as the general public for some of the events. We hope that the Federal President, the Prime Minister of Saxony, and the Mayor of Leipzig will honour us with their presence. Leading scientists from Germany and abroad, including Nobel Prize winners, will give lectures and celebrate with us. And aspiring students of science journalism as well as regional and national media will cover the conference.

As the President, you were able to choose the topic of the conference. Why did you choose “Images in Science”?

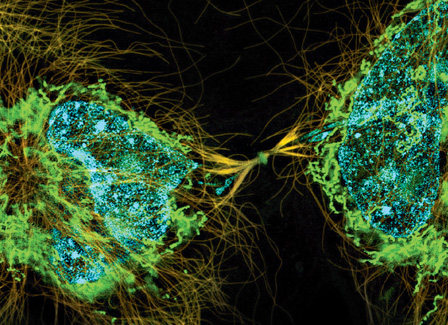

This topic has a general, but also a very personal component. You will find both aspects in the conference. Images have always conveyed central messages in and from science. Let us think, for example, of the many drawings Alexander von Humboldt made on his travels, of the spectacular photos of the North Pole MOSAiC expedition, or of the fantastic images of the space telescopes. In my own research, fascinating detailed images can be produced with new types of microscopes: images of individual biomolecules and from the innermost parts of cells and organisms. The anniversary conference will bring us up to date in this very broad spectrum of images.

Preparations for GDNÄ conferences always take well over a year: topics and speakers are discussed and found, conference logistics are planned, a social programme is organised. We started planning for the anniversary conference a good two years ago, because this meeting should be even more beautiful than usual. We have attracted many excellent speakers from all over the world. The conference rooms in the Congress Hall provide a magnificent setting for the meeting, the cooperation with the zoo is very close and committed and offers many highlights, and the social programme will make the meeting particularly delightful.

Let us turn our gaze back once more. 1822 to 2022, that is a long time: how has the GDNÄ managed to last over so many years?

The two centuries of its existence are without doubt the most exciting times science has ever experienced. Never before have the developments in science, but also those that science brought to society, been so great – and this is true for the entire spectrum of the GDNÄ. Many disciplines were actually born during this time, and they have all evolved into their own specific worlds. The GDNÄ has always been at the centre of these developments, and many specialist societies have sprung from the GDNÄ, and have often become much larger than the GDNÄ itself. However, during all these years, the GDNÄ has retained some unique features.

What are these special features?

Three aspects characterise the GDNÄ and make it unique: First, the GDNÄ cultivates interdisciplinary discussions across a broad spectrum of subjects – in a way that cannot take place in specialist societies. Second, the GDNÄ runs a student programme with great potential for the future. And third, the GDNÄ addresses the general public: with its activities in science communication, via its homepage, and invites citizens of the city and its region to its meetings. We will highlight all three aspects in Leipzig.

View into the Great Hall of the lavishly renovated Gründerzeit building from 1900. The building has a total of 15 halls and rooms as well as foyers and lounges. © Leipzig Trade Fair

What will be the role of young people at the Leipzig conference?

We invite more than two hundred young people: Selected high school students from the region, former programme participants, winners of the “Jugend forscht” and “Jugend präsentiert” competitions. There will be preparatory workshops and a presentation of the results at the opening ceremony. The aim will be to define and express young people’s expectations of science. With this programme, which has been organized by Mr Mühlenhoff for many years, we want to address young people and open up paths to science for them. And, of course, also into the GDNÄ.

The Corona pandemic has shown the importance of the dialogue between science and the public. How has the GDNÄ been involved in this issue?

The Corona pandemic has highlighted both strengths but also weaknesses of our society. The strengths include an incredible number of rapidly produced research results, including, above all, the development of vaccines in less than a year. However, it has also become clear how difficult it is to connect to the entire population, to convey research knowledge. And it has also become clear how much basic knowledge is needed for conversations about the disease and meaningful countermeasures. The GDNÄ aims to provide information about this topic on its homepage, it participated in the discussion about risk-adapted measures at an early stage and, together with science academies and research institutions, aimed to inform politicians. Some of its members participated, for example, in a symposium of the Hamburg Academy of Science on “infections and society”. Together with German science academies, we now want to increasingly devote ourselves to the follow-up and ask address two big questions: How did we as a society and how did science fare in this crisis? And what can we learn from this for the future – for future pandemics and other crises, but also for science communication?

What role will the Corona pandemic play in the anniversary meeting?

Corona will not be the focus at the Leipzig meeting. So much has already been said about it that it did not seem to make sense to us. But RNA medicine, which has brought us the best vaccines so far and opens up completely new opportunities for innovative therapies, will be a central topic of the “Medicine” session on Sunday morning in Leipzig.

What are your wishes for the GDNÄ in the coming years?

Of all the wishes I have for the GDNÄ, one is central: that it may continue to play an important role in the dialogue between the sciences, with the public and especially with young people. And that for 200 more years!

Prof. Dr. Martin Lohse © Bettina Flitner

About the person

Prof. Dr Martin Lohse has been President of the German Society of Natural Scientists and Physicians (GDNÄ) since 2019. In this honorary office, he is responsible for the programme of the assembly celebrating the 200th anniversary. In his main profession, the renowned pharmacologist has been a professor at the University of Würzburg since 1993, and Chairman of the incubator ISAR Bioscience Institute in Planegg/Munich since 2020. His research focuses on receptors and their signals; they represent the most important targets for drugs.

Martin Lohse studied medicine and philosophy at the universities of Göttingen, London and Paris and did his doctorate in Göttingen at the Department of Neurobiology of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry. After working with Ulrich Schwabe in pharmacology in Bonn and Heidelberg, he joined the laboratory of Bob Lefkowitz, who later won the Nobel Prize, at Duke University, where he became an assistant professor. From 1990 to 1993 he was head of a research group at the Gene Centre in Martinsried/Munich, established by Ernst-Ludwig Winnacker. In Würzburg, he founded the Rudolf Virchow Centre, one of the first three DFG research centres, as well as the university’s graduate schools in 2001. After six years as Vice President for Research at the University of Würzburg from 2009 to 2015, he was Chairman of the Max Delbrück Center in the Helmholtz Association in Berlin from 2016 to 2019. He has received numerous awards, including the DFG’s Leibniz Prize, the Ernst Jung Prize for Medicine and two grants from the European Research Council. He has co-founded four biotechnology companies. Martin Lohse has held numerous honorary positions in science in Germany and abroad; amongst these, he was Vice President of the National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina from 2009 to 2019.

Congress Hall Leipzig exteriorThe Congress Hall at Leipzig Zoo is a modern conference centre in a historical ambience. © Leipzig Trade Fair

Weitere Informationen: